COVID Contact Tracing and Tracking: Canada’s Scandalous Missed Opportunity

The Issue

One of the defining differences in how countries of the world have attempted to mitigate the pandemic is contact tracing. Most countries like Canada, the U.S. and most of Europe have focused their strategies on ever-renewed, tweaked, one size fits all, lockdowns. A group of others, including Singapore, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, have largely kept most businesses and schools open by emphasizing and rigorously applying comprehensive contact tracing and tracking. They use lockdowns as a last resort, when needed.

This blog addresses three questions:

- First, is contact tracing a new infection-fighting public-health strategy?

- Second, just how badly underused and mis-managed has contact tracing been in Canada?

- And third, could there ever be a workable, effective and cross-border, international standard?

Contact Tracing: Theory and Practice

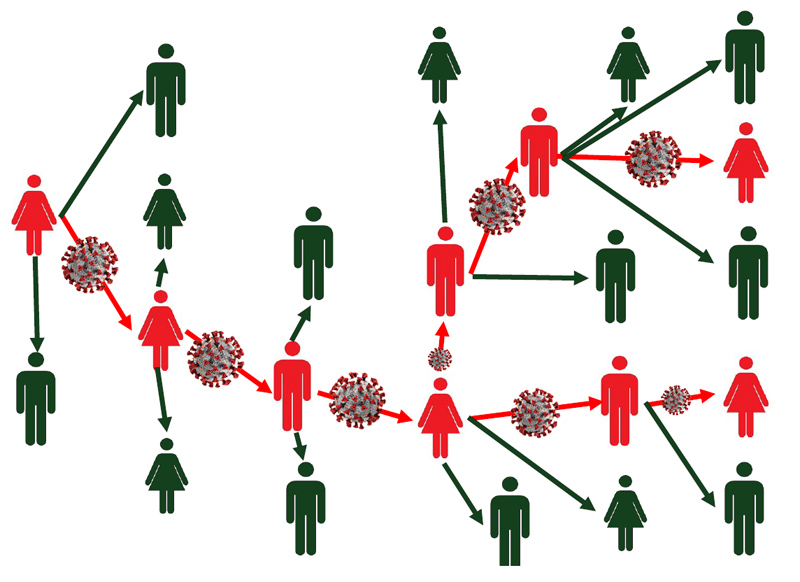

Contract tracing as a public-health strategy is built on a simple idea: When someone tests positive for the new coronavirus or becomes sick with COVID-19, you find all the people the infected person came into contact with, because they too, may be infected. You than follow this up by investigating outbreak clusters, providing safe quarantine places, and providing financial compensation.

Contact tracing is a tried-and-true method that epidemiologists have been using for decades to tackle everything from food-borne illnesses to sexually transmitted diseases, as well as recent outbreaks of SARS and Ebola. It’s a great tool for bringing an epidemic into the suppression or containment phase. It is:

- (a) strategic,

- (b) applied vigilantly when and where needed; and

- (c) doesn’t replace other public-health strategies and measures.

What it does not do is precipitously close down or sequester entire categories of businesses, schools, and available ICU hospital beds.

The textbook version of contact-tracing starts with someone testing positive for COVID-19 and isolating themselves. A contact-tracer interviews this person to find out who they might have exposed while infected, usually from 48 hours before the positive test, or before symptoms appeared (if there were any). Close contacts — those who’ve spent more than 15 minutes close to the infected person — are of special interest, but anyone who shared public transport or an office space might qualify. Tracers then call or visit those contacts to tell them they need to quarantine, so that they don’t pass the virus on to more people. Conceptually, then, the chain of transmission is broken.

In reality, failures occur at every stage of this test–trace–isolate sequence. People get COVID-19 and don’t know it, or delay in getting tested. Positive results can take days to be confirmed. Not everyone who tests positive isolates when requested. People can’t always be reached for an interview or don’t provide details of their close contacts. And not all contacts are reached, or are willing to comply with a quarantine order. Because of this range of problems, researchers estimate that in a country like England, tracers typically reached less than half of the close contacts of people who’d had a positive COVID-19 test. There are no readily available data for Canada on our number of “missed contacts” or how many of these contacts actually quarantined in turn.

Contact Tracing: International Practice Variations

As the map suggests, a handful of countries stand out as exemplars of successful comprehensive (all cases) contact-tracing. They include South Korea, Vietnam, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, and Australia. These countries cracked down on COVID-19 early, isolating infected people and their contacts, and used personal data such as mobile-phone signals to track compliance. Their rates of COVID infection and per capita deaths are typically one tenth to one twentieth that of Canada.

Singapore and Australia have done a massive amount of testing per case. Highest numbers of tests per confirmed cases for select countries include Singapore (4,062), Australia (3,848), Taiwan (104) and South Korea (100). By contrast, robust economy countries with mediocre numbers of tests per confirmed cases include Canada (25), Germany (20), Sweden (19), the U.S. (14) and the U.K. (12).

Success and Inhibition Factors

Researchers identify a series of factors, including contextual, behavioral, legal and technical ones, that may impact the success (or effectiveness) of any evidence-based, digitally-reinforced contact tracing initiative during the pandemic. They include:

- The general set of healthcare mechanisms (context) established by a Government and, particularly, Public Health Authorities.

- Early coordination to identify and isolate infected individuals requires acting early, quickly and decisively.

- Availability of trained and aware personnel—particularly at primary-care centers.

- Availability of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) for health-care professionals.

- Massive use of face masks, physical distancing, self-isolation, travel restrictions, and specially, widespread testing and rapid results.

That said, there are a number of issues that may prevent or inhibit contact tracing adoption rates:

- a) unavailability of appropriate devices (in some regions or segments of population);

- b) unawareness on the existence of the app (due to insufficient publicity);

- c) no access to the app (due to restrictions imposed by app-stores) even before certain potentially malicious pieces of software may be discovered;

- d) lack of tech-savvy citizens (such as elder people, minorities, or vulnerable groups at risk of financial/social exclusion);

- e) lack of transparency;

- f) lack of engagement from and trust by citizens;

- g) privacy and interoperability (cross-boundary) challenges.

Even among countries that are leaders, variations exist in specific techniques and practices, depending on the country involved. This includes details like:

- (a) willingness to publicly post data identifying infection-suspect individuals;

- (b) issuing contact traceable wearable devices;

- (c) mandatory use of tokens or an approved contact tracing app to facilitate digital check-in procedures at some locations where “higher-risk activities” are held;

- (d) willingness to collaborate with High Tech developers, many in the private sector; and

- (e) whether the personal data collected can only be extracted when devices are physically handed over to a health official.

According to consulting firm McKinsey, three themes emerged as critical enablers of successful decision making and action in Australia:

- building trust with citizens;

- using data-led decision making; and

- fostering effective collaboration across boundaries.

Not all of these techniques are transferable to countries like Canada, the US, and the UK that continue after a year to struggle to contain massive infection wave outbreaks. But they still provide some important lessons about missed opportunity and political leadership. Our national and provincial governments have never asked Canadians if we would be willing to have some invasion of personal privacy with GPS tracking in order to reduce the substantial limitation on civil liberties we have had to endure in the absence of comprehensive tracing.

Canada’s dismal experience with tracing and tracking can be summarized as follows:

- most provinces and territories have hired too few contract tracers;

- the federal voluntary self-reporting digital device platform had design and roll-out flaws from the start;

- there have been widely subjective and inexplicable changes in administrative regulations that represent holes in the system (such as the subjective number of allowable minutes serving staff are in contact with restaurant patrons);

- public-health messages are largely silent about convincing someone they should pick up the phone when a contact tracer calls;

- there is little or no non-partisan collaboration between the federal and provincial/territorial governments;

- while hundreds of restauranteurs are required to keep lists of patrons for prospective tracing if necessary, most admit that no one from a health authority ever collects these data; ideally public health is supposed to follow up but it is often patrons, not health authorities, that do;

- Early decisions were not made on priorities about whom should be tested: for example, the vulnerable, health-care providers, essential-care workers, dangerous workplaces like abattoirs, shelter residents, and/or other populations. At times, Ontario allowed anyone who wanted one to be tested;

- there are hundreds of Facebook posts and YouTube videos spreading hoaxes and lies about contact tracers that have received hundreds of thousands of views.

A Universal System

The reasons for contact-tracing failures globally are complex and systemic. Antiquated technology and underfunded health-care systems have proved ill-equipped to respond. Wealthy nations have struggled to hire enough contact-tracers, marshal them efficiently, or make sure that people do self-isolate when infected or that they quarantine when a close contact has the disease. Overstretched contact-tracers have been met with distrust by people wary both of health authorities and of the technologies being deployed to fight the pandemic. Meanwhile, researchers who are keen to draw lessons from contact-tracing operations are stymied by a dearth of transferable national and global data.

The consortium ETSI and its “Europe for Privacy-Preserving Pandemic Protection” (E4P) group last month releasing its first Report GR E4P 002, entitled “Comparison of existing pandemic contact-tracing systems”. The Report includes the characterization of a representative series of apps, from among those currently available, ranging from the United States to Japan, as well as a list of the most relevant existing digital contact-tracing methods. The study also offers a comparative analysis of these different methods and outlines a series of challenges that are yet to be tackled to support a global system.

ETSI E4P Industry Specifications Group (ISG)’s next steps are focused on finalizing the definition of the general requirements of this type of solution; conducting an analysis of the mechanisms related to the devices (essentially smartphones) used; specifying the requirements of the back-end systems involved; and, finally, releasing a reference framework for the interoperability of the different existing digital tracing methods. Future stages will evaluate how to improve the systems specified and explore and develop new ones.

Conclusion

A robust comprehensive contact tracing program should be an integral part of fighting the coronavirus. Canadians have paid an unnecessarily high price because our political leaders have underfunded, under-estimated, and under-appreciated the benefits of comprehensive contact tracing.

Need More Answers?

Subscribe to the EthicScan Knowledgebase for in-depth research and the opportunity to share information with industry experts, policy-makers and other health-care professionals.

Sign up for New Blog Alerts

Sign up here for free new blogs to be sent to you

Further Reading

EthicScan Blog – The Future: The Ethics of Tracking:

http://ethicscan.ca/blog/2020/05/21/the-future-the-ethics-of-tracking/

European Telecommunications Standards Institute – ETSI unveils its Report comparing worldwide COVID-19 contact-tracing systems – a first step toward interoperability:

https://www.etsi.org/newsroom/press-releases/1879-2021-02-etsi-unveils-its-report-comparing-worldwide-covid-19-contact-tracing-systems-a-first-step-toward-interoperability

Nature – Why many countries failed at COVID contact-tracing — but some got it right:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03518-4

EthicScan Blog – Testing and Contact Tracing Challenges and Choices:

http://ethicscan.ca/blog/2021/02/04/testing-and-contact-tracing-challenges-and-choices/

Government of Canada – Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology update:

https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html

Brookings – Digital contact tracing and the coronavirus: Israeli and comparative perspectives:

https://www.brookings.edu/research/digital-contact-tracing-and-the-coronavirus-israeli-and-comparative-perspectives/

EthicScan Blog – Recovery Choice Planning Part One: Testing & Tracing:

http://ethicscan.ca/blog/2020/07/08/recovery-choice-planning-part-one-testing-and-tracing/

The Street – Contact Tracing is a Huge Success So Why Won’t The US Use It?:

https://www.thestreet.com/mishtalk/economics/contact-tracing-is-a-huge-success-so-why-wont-the-us-use-it

EthicScan Blog – It’s Time For A Different Approach to COVID: PART ONE:

http://ethicscan.ca/blog/2021/01/25/its-time-for-a-different-approach-to-covid-part-one/

The New York Times – Contact Tracing, Key to Reining In the Virus, Falls Flat in the West:

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/03/world/europe/covid-contract-tracing.html CAN’T GET IT falls flat in west

McKinsey – Collaboration in crisis: Reflecting on Australia’s COVID-19 response:

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/collaboration-in-crisis-reflecting-on-australias-covid-19-response#

- Belief and COVID: Is COVID Part of God’s Plan? - April 12, 2021

- COVID Contact Tracing and Tracking: Canada’s Scandalous Missed Opportunity - March 26, 2021

- Boredom, Vaccine Fatigue, Mental Health and COVID: Enhancing Morale/Finding Meaning - March 24, 2021

I was hesitant to use the government’s covid app because I didn’t want to give up my privacy.